The piece references the Roman proverb “better the devil you know than the devil you don’t,” aiming to highlight how this saying permeates and conditions various aspects of Ecuadorian social, emotional, personal, and political life. Traditionally a call for caution, it can also be interpreted as a form of resignation in the face of change. By inverting both the television set and the proverb itself, the work seeks to subvert its culturally ingrained meaning, proposing a shift from ‘reserve’ to ‘audacity’. The viewer is thus confronted with the challenge—and responsibility—of taking risks rather than remaining trapped in the precarious familiarity of the known.

In Ecuadorian culture, this saying is frequently used when referring to those in power or public office. It also emerges in discussions around work, relationships, and emotional bonds, where negative situations are often maintained for fear of a potentially worse alternative. More than a popular saying, the proverb acts as a cultural mechanism that reinforces the belief that any attempt at change brings with it an even greater threat.

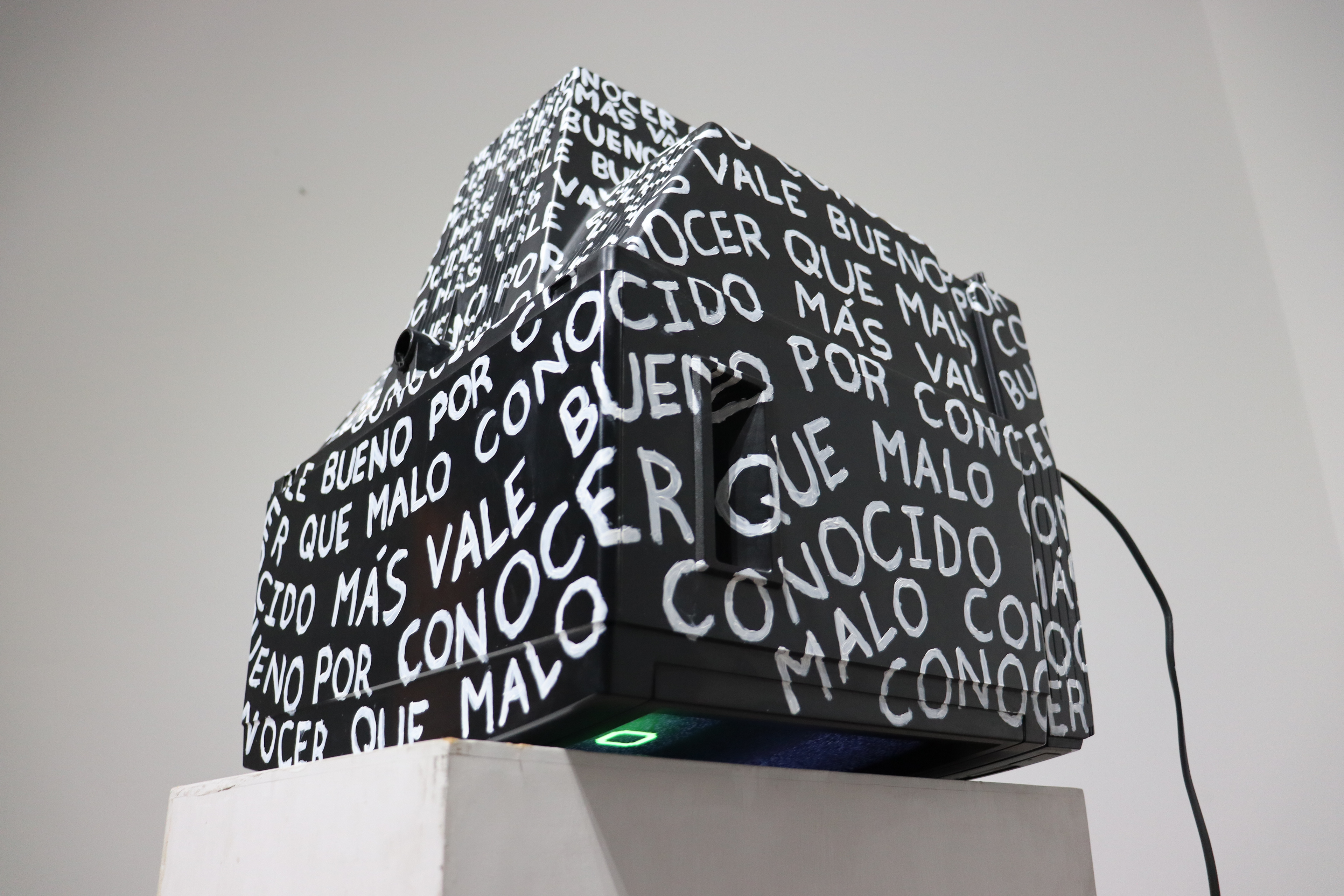

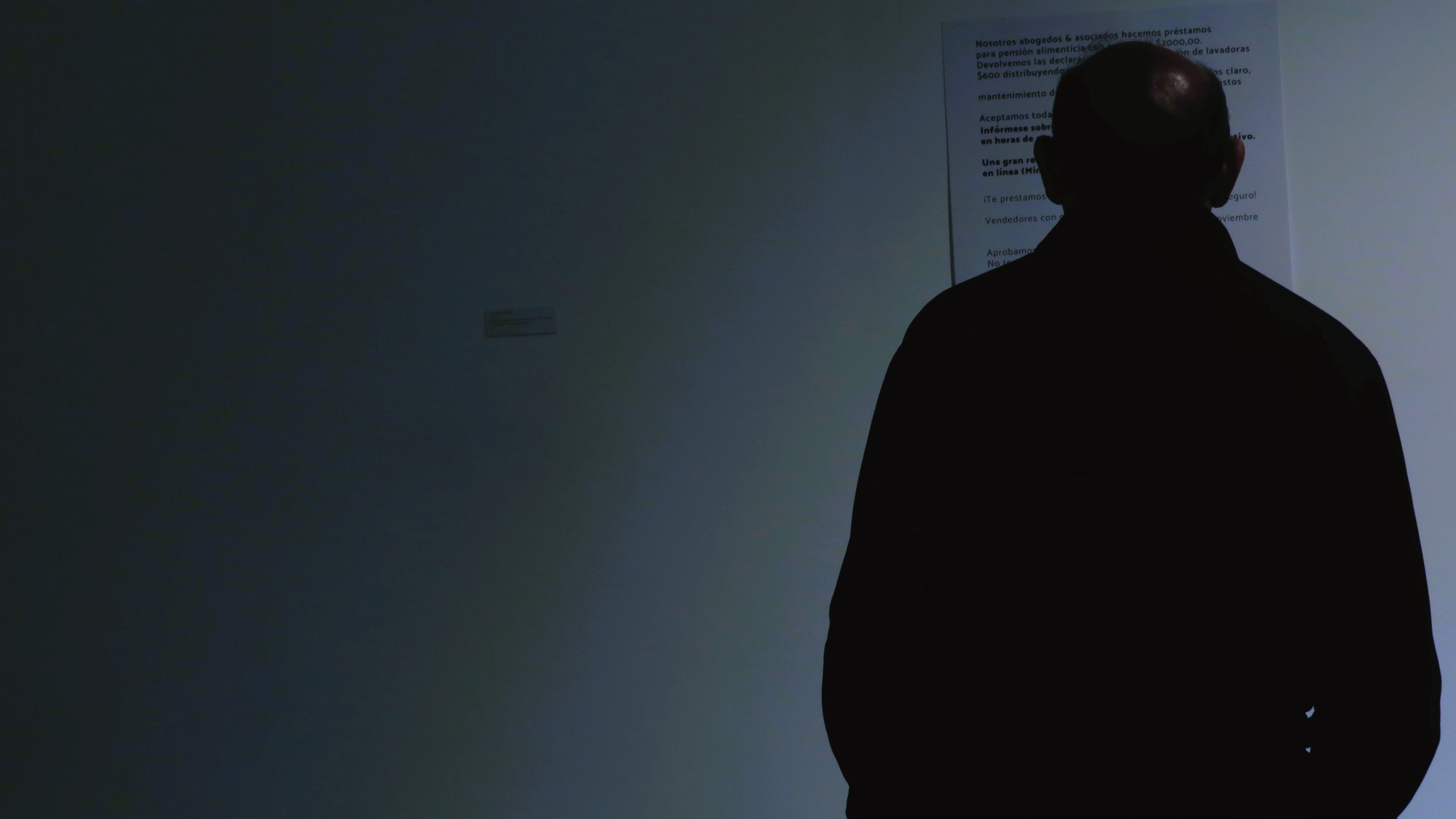

The piece consists of a switched-on television set, altered by the addition of the proverb, handwritten in white acrylic. This gesture draws on the tradition of the ready-made, in the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, who recontextualised everyday objects to generate new meanings. In this case, the television represents the media—an influential force in shaping public perception of the present and of change.

The inscription across the image borrows from conceptual art, using language as a direct point of access to the work’s content. This choice allows viewers to engage with the piece without requiring prior technical knowledge, encouraging broader and more personal interpretations. The positioning of the text, coupled with the sound of TV static, creates a sensory experience in which visual noise challenges the viewer to reconstruct the proverb based on their own social, political, or personal realities.

Rather than offering a definitive answer, the work invites a question: in the face of change, do we choose conformity and caution, or boldness and bravery? The inversion of both the television and the proverb suggests that even small shifts in perspective can produce real transformations—and that it is possible to imagine and build better alternatives without allowing fear to stifle the desire for change.